1896-1900. Her beginnings.

Fernand Crouan

Mr. Fernand Crouan was a small corpulent man, in gold rimmed glasses, very well-known in the bourgeoisie of Nantes. From his offices on the street of Héronnière, he handled his business, mainly the commerce of Pará’s cocoa and sugar from the Islands for the famous Menier chocolate factory. He moved around the city in a black cabriolet with red lines, the colours of his vessels.

From 1890 to the liquidation of his company, he possessed the following sailboats, all built by the shipbuidling yard Dubigeon:

- Cruzeiro,

- Brazileiro,

- Pará, 1888, (name of a state of Brazil, one of the rainiest, where is located Belém and its port on the estuary of the river Pará),

- Noisiel, 1890, (an old eastern Parisian town where were located the Menier factories. It was the first three master of the armament with iron hull),

- Claire-Menier, (mother of Henri Menier, the customer of the shipowning company for the cocoa and the sugar),

- Denis-Crouan, (ancestor of Fernand Crouan, founder of a counter on the northern coast of Brazil in 1817),

- Belem, 1896, (name of capital city of the Brazilian state of Pará, near the mouth of the Amazon, contraction of Bethlehem),

- Émile-Menier, (Émile Justin Menier industrialized in 1852 the manufacturing of chocolate. He was the son of Jean Antoine Brutus Menier, founder of the Noisiel factory, and father of Henri Menier, the customer of the shipowning company for cocoa and sugar).

The pavilion of the shipowning company Crouan was white with red edges and contained a red star in its centre.

On the bow of the Belem appeared then a motto in portuguese: Ordem e progresso. This motto, Order and progress, chosen by the young Republic of Brazil, proclaimed in 1889, was inspired by Auguste Comte’s positivism. It correspondeded also well to Fernand Crouan philosophy whose vessels were for the greater part in steel and always meticulously maintained.

The Belem was the seventh three-master ship of Crouan’s shipowning company.

At Mr Crouan’s death, his son-in-law took over business but Menier decided to get its cocoa through le Havre, a closer port. Deprived of its usual freight and undergoing fierce competition from steamers, the shipowning company was liquidated in 1906. The Belem was then acquired by the company Demange Frères for their line serving Cayenne.

1896, birth

Fernand Crouan ordered the Belem to the shipbuilder Adolphe Dubigeon in 1895.

The Belem was a small boat if compared to the majority of the ships produced at that time. Unlike most of her colleagues with sails, she wasn’t intended for circumnavigation or cap passages. She was especially created to transport cocoa and sugar from Brazil and the West Indies to Nantes for the main Crouan’s customer, Henri Menier’s chocolate factory located in Noisiel. This kind of boat was called “Antillais” from Antilles, West Indies in French.

“Being registered as a French ship in Nantes in 1896. Nb 3377. Armement Denis Crouan Fils”. Picture from the Museum of Salorges in Nantes presenting the Belem in her original state. The flag with Crouan’s colors and star floats on the mainmast.

No more than 7 months were necessary to build her. Shipyards were very active in those times. The construction of French steel sailboats was being doped by the premium for navigation of 1893 (which was applied by covered mile and by ton of gross tonnage), and by other incentives, without counting on the increase of the freight connected to worldwide economic development. In spite of the apparition of steamers that trusted the traffic passengers and mail, it was really the golden age of sail. Boats reached affected a certain technical perfection and they were never so numerous on the seven seas. They were successful and very economic for heavy cargo like coal, nitrates, cereal, etc.

The sailboat was delivered to her shipowner on July 30th, 1896.

Known among the sailors of my time for her elegance, her impeccable maintenance and her beautiful and fine silhouette, the Belem was built in Nantes, in the shipbuilding yards Dubigeon, for Mr. Fernand Crouan, the shipowner well known by this place, which intended her for the journeys to Pará (Belem in Brazilian) and the West Indies.

Ordered in December, 1895, she was delivered to her shipowners on July 30th, 1896 and had been registered as a French ship ten days before. Built in steel without orlop, lined with a deck in pitchpin, it was a well-deck vessel with a poop and a forecastle, carrying in full load six hundred and seventy-five tons for a corresponding draft of four metres fifty seven, with a cubic capacity of one thousand hundred fifty cubic meters, the gross registered tonnage was five hundred and fifty one barrels sixty three for a gross tonnage of five hundred and twenty seven barrels seventy-two and a net capacity of four hundred and fifty five barrels thirty two. She had four panels of load instead of three, the biggest of which was four meters sixty one long and three meters zero five wide and its dimensions were the following ones: length fifty metres ninety-six, width eight metres eighty, hollow hold four metres fifty seven following le Véritas on the register she was registered for her first classification. Masted in three masted barque with topgallant, royal and double topsails, she had a wooden masting containing top masts and topgallant masts of a single piece and a bowsprit without jib-boom. A windlass and a fly-wheel-pump of rather recent invention, an hand-power winch completed her organization. [Louis Lacroix, 1945].

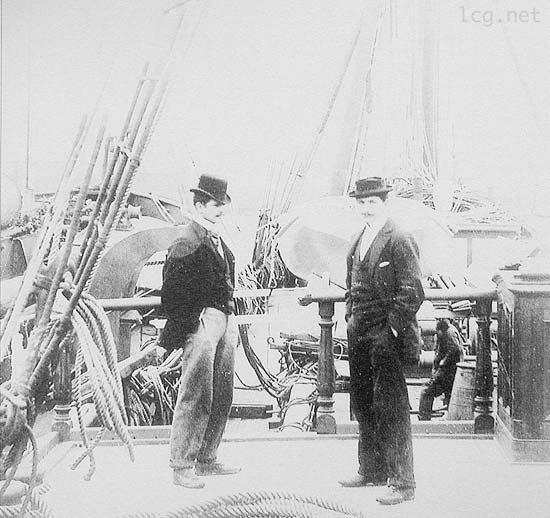

Maurice and Roger, sons of the builder Adobe Dubigeon, posed on the poop of the Belem. One recognizes the same wooden balusters as those that remain at present time on the forecastle. To the right, a hatch cover.

Document: Acte de spécification du Belem (1895).

1896-1897, first voyage

In July 31st, 1896: the Belem left Saint-Nazaire in ballast for the capital of Uruguay, Montevideo, under the command of his first captain, Mr Lemerle, known as “le merle noir” or the blackbird. It was the last command of this fifty-year-old man that would retire when returning to Nantes.

The boat is foreseen for a crew of 12 men: a chief officier, a boatswain, a cook, 8 sailors (4 men of the port watch and 4 men of the starboard watch ) and finally one ship’s boy. With the captain and an apprentice possibly, it could total 14 men. The cook lived in front under the forecastle. The crew’s accommodation for the boatswin and the sailors, was located in the deckhouse where was also located the kitchen. All others were more comfortably installed under the poop.

September 20th: the boat arrived at Montevideo and took care of a load of 121 she-mules to the Belém’s port, a city of the province of Pará in Brazil. Very cumbersome load for which it was necessary to fit out parks in the hold and that asked daily extra work to the sailors.

October 16th: the day after getting under way, a strong gale, the pampero, obliged the captain to scud, under foresail in reef, fixed topsails and inner jib. The pampero is a wind coming from the Andes blowing generally during the summer season. It passes over Pampa towards the maritime coasts (where it took its name from). It is a very dry and cold South/Southwest wind with squalls.

The she-mules of Pampa were not used to the violent rolling… Once, the crew could finally open the hatch covers and inspect the park, they discovered a spectacle of desolation: six she-mules died crushed and trampled, and the others suffered from hardship.

November 15th: 30 days after her departure from Montevideo, the Belem arrived for the first time of her career at Belém.

In berth, on Rio Pará, the vessel waited for a long time for the inspection of the customs and the veterinarian services. In the night of the 16, the men were woken by the noise of she-mules in the hold. A fire broke out. The fight lasted till early in the morning. The 115 surviving she-mules from the pampero suffocated and died quickly in the fire. Shortly after, the crew should battle with the port authorities.

This first campaign of Belem was a disaster. The boat wasn’t able to charge any cocoa for Nantes and the damages were important.

After emptying the hold of its carrions and its ashes, cleaning it, making some makeshifts and setting ballast, the damaged ship resumed her road towards Nantes which she reaches after 46 days of crossing in difficult wind on January 26, 1897.

The boat joined then the ship yard Dubigeon where where will be done the repairs after an examination from the insurers.

On this first journey, we have Louis Lacroix’s testimony, ocean trade captain, which based its story on the information given by its colleague Julien Chauvelon, captain of the Belem for numerous years. We also know that Louis Lacroix had access to various documents relative to this journey (he quotes a sea report).

She left Saint-Nazaire in ballast on July 31th, 1896 to Montevideo, where it arrived September 20th after fifty days in sea and left it on October 15th, having on board one hundred and twenty one she-mules for Pará. Captain Lemerle, nicknamed “Le Merle Noir” (Blackbird) of which I shall speak again farther, had taken command of her at the shipbuilding yards and had only of bad luck.

Just the day after her departure, one of these tremendous squalls known under the name of “pamperos” and special in the estuary of Plata, came down on the vessel. At five o’clock in the evening, the sea was raging; scuding under her foresail in reef, her fixed topsails and her inner jib, the Belem, ruling in the blade, knocked by violent rolling making more than one afraid for her masting.

In the hold, the terrified and tumbled animals, breaking their halters, passed over their mangers by bitting and stamping each other. These storms are of short duration, and, early in the morning, it was possible to open the panels of the hold, which had been condemned because of the fury of the storm: they found six dead and half crushed animals.

Thirty days later, without other worth-mentionning incident, the three-master of Nantes cast anchor in natural harbour of Pará, ready to discharge her load two days later in the morning, as soon as the Customs and the Health would have given the authorization. In the night of October 16th, in spite of frequent rounds, a fire burst out in the parks of the orlop and spread with a speed such that all means used to fight it were ineffective and it was impossible to save one of the hundred and fifteen poor she-mules locked under the bridge.

The sea report which I have under my eyes made clear that the emergency help required by signals to ground was slow to come and that after the fire had been put out after long efforts, the customs and its helpers took advantage of it to plunder the vessel from top to bottom, in spite of the resistance of the captain and his crew which were forced to go ashore.

After important temporary repairs, the Belem took ballast to return to Nantes, where the insurers had decided with the shipowners that she would be repaired completely. Out of the Northeast trade winds region, Captain Lemerle found big variable West winds that make the crossing painful, obliging to maneuver sails constantly and to modify them according to the irregular force of the breeze. The pilot of the Loire embarked on board only on January 26th, 1897, after forty six days of crossing and Mr Lemerle, who had gained his pensions and exceeded fifty years of age, withdrew in his region, leaving command to Captain Rioual. This one followed the repair works and, as soon as they ended, came to the quai de l’Aiguillon and embarked pavements from Sainte-Anne’s career, to serve as ballast to return in Montevideo for a second time. [Louis Lacroix, on 1945].

[This text contains a strange error: the fire is dated October 16th instead of November 16th. It is an impossible date because the boat left Montevideo on October 15th. We don’t know if it due to an inattention of the author or a misprint left by the publisher.]

Jean Noli, in the text of the album Le siècle du Bélem published in 1996, give away a version which differs by certain points: he indicates for example a crossing of 75 days to rejoin Montevideo (instead of about fifty days), what seems to be a mistake (he confused probably the arrival date to Montevideo, on September 20th, with the departure date of the same port, on October 15th). He speaks also about “a brief stopover in Montevideo” while it lasted 25 days… As for the story of Belém’s incidents, he takes up again more or less Lacroix’s indications.

Daniel Hillion, in its book Le Belem, cent ans d’aventure, proposes a version of this story very different and richer in explanations, a history which seems more true and more realistic in all respects. The author had access probably to others sources than those of Louis Lacroix (Jean Noli manifestly took up his story according to Lacroix’s testimony). We can also think that the old captain Lacroix had hesitated to tarnish the memory of Captain Lemerle by corporatism and allegiance in a certain spirit of La Marchande. Or more simply than Chauvelon passed on him only the “official” story as testified in the sea report.

So, here is the summary of the story astold by Daniel Hillion of this somber and disastrous (for the she-mules) first journey :

On July 31st, 1896, Belem leaf Saint-Nazaire’s natural harbour. On board, the captain Lemerle, known as le merle noir (blackbird), and Alphonse Rio, the young 23-year-old chief officier. Hillion lets us understand that the relation among these two, the one that is soon going to take his pension after a well-filled life, and one young, fiery and inexperienced officier, is strained at least. Lemerle was, it seems known, as much for his hardness towards crewmen as for his scorn of young officers.

Charged with she-mules from Montevideo which survived the pampero, the boat arrived in Belém on November 15th, the day before a holiday, and had to remained for two days anchored on the river waiting for the visit of the customs officers and the health service. The crew took charge of current maintenance on the vessel and set back on foot the weakened she-mules.

The fire broke out in the night of the 16th to the 17th. Fed by the litter straw, it spread very quickly in parks. In front of the failure of the first fight attempts, there was nothing more to do except to close hatches and to seal ventilators. Help was asked to ground by light signals, but it dawdled on the way.

Lemerle, woken by the hullabaloo of she-mules, boiling with rage, take it out on his own son, a 18-year-old, embarked young man as an apprentice. He needs a culprit! The chief officer, Rio, took the defence of the apprentice and Lemerle turns against the boatswain, who will desert next night in the matter of fact, leaving clear field to suspicions, justified or not.

Fire brigades arrived finally. Panels were opened, reviving the fire which begins to spread on the bridge. After a long fight, the fire is brought under control early in the morning. All the she-mules died for a long time, were half carbonized.

The vessel is tugged to quay. Just after the manoeuvre completed, the sailors announced that they were going to do a tour in town. Captain Lemerle didn’t believe its ears. “And the protests of the captain, his orders, the threats changed nothing. The captain, so authoritarian he was on sea, was not any more the incontested master on ground. The sailors know, besides, that it was easier for them to find another embarking than for the Captain Lemerle to get a new crew for a damaged vessel.”

The sailors left the boat, and Lemerle, full of fury, ordered the chief officer Rio to follow him it in town for bring back the men. Rio refused this order which would have for result to leave the vessel without surveillance while fire brigades were already quarrelling over the plunders of the Belem. We imagine the effect of the insubordination of this young officer on the old captain…

The Crouan’s representative arrived and put an end to the quarrel among them. He thought as Rio that a damaged and immobilized vessel alongside quay was going to attract looters. He invited the captain to go run aground in river and to throw the she-mules in the water before they stank.

Hours later, the sailors returned and agreed to embark provided access to food and drink in good quantity. A guard duty is established just the time to get food and to take advantage of the city’s pleasures until the next day.

The boat was brought to the rio Tocantin where began the macabre evacuation work of the hold and the first repairs. Lemerle did not leave his bad mood, especially since his son abandoned the boat to take refuge on the other one the dat before. Furthermore, his young chief officer, Alphonse Rio, gave him still evidence of insubordination by refusing to modify certain passages of the ship’s log unfavourable to Lemerle. It is too much for him! Lemerle came to blows and the affair was settled with fists. And it was the old man who had the upper hand! But this physical victory didn’t succeed in imposing a rewriting of the ship’s log…

After cleaning the hold and consolidation works of lower masts, the Belem was anchored in the mouth of the river looking forward to favorable wind conditions. At dawn, on order of the second officer, the new boatswain called “Up the hammocks” to the crew. And when Lemerle came to give the order to heave out sails, nobody is at his post. When Rio get the man of the watch asking for explanations, he only got this reply : “Sir, both watches are asleep.” They were close to a rebellion at this moment.

A real wrestling match began between the crew and Lemerle. The sailors want to return to Belém, argueing the bad state of the ship, and asking for other repairs. The captain then decided to cut them foods and threatened to use fire weapons at the slightest uprising. More than forty eight hours after, the boatswain comes to the rear with the new of the surrender. “The men are prepared to obey orders but they ask to eat. — Not before we are at sea; the captain retorted.” It will be necessary to wait another 24 hours for the arrival of favorable winds to sail and finally men to eat in the crew’s quarters.

No doubt that Melville, or Conrad, would have been able to write with brio a striking story of this pathetic voyage with heroes like Rio and Captain Lemerle…

1897, second voyage

As soon as repairs ended (following the important fire in the hold of the first journey), the Belem took a load of pavements from Sainte Anne’s quarries, to serve as ballast, to go to Montevideo. A new 26-year-old captain was appointed, François Rioual. It was the first command for this young man native of Binic that had just obtained, one month earlier, its fully-licensed captain’s patent from Paimpol’s hydrographic school. Rioual had got up all the rungs of the Merchant nav : he began as ship’s boy, at the age of 12 years, on the three-master barque Le Penseur.

She left on March 11th but the next day the wind strengthened. The outer jib was torned. The boat and the crew had to support difficult conditions until March 19th. They crossed the Equator on April 15th, ritual passage which gave place to the baptism of 5 sailors (among which the young Rioual’s brother, Louis, embarked as ship’s boy).

On May 4th and 5th, the boat faces a bad blow of pampero off the Uruguayan coasts.

Arrived on May 7th, the Belem embarked in Montevideo not only she-mules as in its first journey, but also sheeps (an ewe gave birth to a lamb during the voyage), and naturally of all that was neede to feed that flock. The departure was set for May 30th.

François Rioual noted the extra work caused by her lively load on the log book:

“The men embarked 82 bags of bran, 529 balls of hay, 704 balls of alfafa, 828 bags of corn, 18 ornamental lakes for animals. A hospital was installed to look after them.”

“In June 14th. 11. 30. A she-mule falls. No one can lift it. Put this animal in the hospital where its legs were rubbed with some camphorated alcohol. Its drinks and eats but refuses to get up. Midnight: the she-mule dies without having given any sign of suffering. Five men shad to fuss around to throw it over board.”

“In June 18th. At horrible night for animals. Violent rolling. A second she-mule put in the hospital has an abscess in the eye as a result of a bite. Need eight men, to put the animal on the belt to maintain it up. Otherwise it will die.”

“In June 19th. A she-mule falls but is not sick: no one can approach it . It bites everybody.”

“In June 20th. The she-mule having an abscess dies. The men tired out to get it up on the bridge and to throw it to the sea.”

“In June 24th. 8. 45. A she-mule begins to bleed of the nose. We can stop this bleeding only at 11 o’clock. It lost 4 liters of blood. It goes well and has good appetite.”

As the ship’s log can testify, the hundred and eleven she-mules don’t really appreciated the navigation conditions and some of them had died before the arrival to the Belém’s port on June 27th.

The accosting turned out badly, the Belem runs aground. It will be necessary to wait two days before the tide could free the boat.

“Smothering heat. She-mules fall as flies.”

We unloaded the survivors on June 30th: 99 she-mules, 63 sheeps and ewe and the 7-days lamb. Then we repaired the hold.

For her return towards Nantes, the Belem took her first load of Brazilian cocoa (4210 bags).

The boat left Belém on July 14th and after 38 days in sea, reached the estuary of the Loire. She was held 24 hours for disinfection to Mindin’s lazaret, because of a yellow fever epidemic.

Story of this journey by Louis Lacroix, ocean trade captain:

“Fifty-nine days after her departure, she arrived at destination [Montevideo] and embarked a hundred and eleven she-mules plus sixty five sheeps again for Pará [Belem]; she arrived there on June 27th, 1897, after twenty eight days in sea and having lost eight she-mules following the bad weather that occurred during crossing. After landing of her load and being load at full capacity of cocoa for Nantes, she sailed for this port from which she obtained practice on August 21th, when she had been disinfected in the Mindin’s lazaret, where all bedding objects on board were burned by order of the Health because of the yellow fever which reigned in Brazil at the time of its departure of Pará.” [Louis Lacroix, on 1945].

Capitain François Rioual.

Jean Noli, in the text of the album Le siècle du Belem published in 1996, delivered a romanced portrait of the young captain:

The three-master barque Le Penseur was his first embarking. He was only 10 years old and he was ship’s boy. At 15 years old, he was named ordinary seaman before becoming a sailor four years later. His military service in the Royal, as gunner, lasted 24 months. At 24 years old, when he began studies to become an ocean trade captain, he had already lived eleven years and three months on boats. In 26 years old, he picked up his master’s certificate of ocean trade captain. On February 17th, 1897, François Rioual, of Binic, receives his first command: the Belem.

He is a robust, powerful, calm, authoritarian but just man. He knows the sailor’s life. A life spent to slave away on the bridge or in masting. Every muscle of its body had strengthened due to maneuvering. He knew the cold, the suffering and these oppressive silences, at the crew’s quarter, ears on watch while storms shook badly the vessel. He learnt to respect the men, those that dare to face the ocean’s furies. He chose with care his crew. His chief officer is Barillec from Damgan. The boatswain is named Le Port from Carnac. The crew consists of Dupont, an inhabitant of Nantes, a cook; Rival from Saint-Malo; Le Port from Lorient; Celu from Vannes; Trionnaire from Nantes; Chanteau from Noirmoutier. They are sailors. Bertie from Étel, and Lesquelen from Étables-sur-mer are ordinary seamen. Canivet, from Pont-Aven, and Louis Rioual, from Binic, the captain’s young brother are ship’s boys.

1897-1899, third to fifth voyage

1897-1898, third voyage

The old captain Dolu took command for this third campaign (Rioual being henceforth appointed to the Denis-Crouan).

The boat made its first stopover in Cardiff to get a load of Welsh coal for Buenos-Aires.

After unloading coal and cleaning of the hold in Buenos-Aires, the Belem headed for the third time towards Belém, loaded once again with she-mules, sheeps and general goods. She would return to Nantes with a full load of Brazilian cocoa.

A veteran of the Crouan’s company, Captain Dolu, ally of my family, relieved a tired Mr Rioual and led to Cardiff the Belem, where she took in this port a load of Welsh coal for Buenos Aires, where it arrived on December 11th, 1897, counting sixty seven days in sea. After thirty seven days used in this port to unload coal and to embark forty she-mules and as many sheeps as well as different goods for Pará, she left the estuary of Plata on January 19th, 1898, made a crossing without incidents and a fast expedition for Belem, she took there her a full load of cocoa for Nantes where she arrived forty five days after her departure from the Amazon. [Louis Lacroix, 1945].

1898, fourth voyage

This fourth journey looks like the third one but without a stopover to Cardiff.

Captain Dolu did in Nantes only a short stay of half-month, resuming sea on May 18th for Buenos Aires. On July 1st, she was in this port, left it the 20th with a complete load of general goods, two dozens of sheeps selected for Pará, and six she-mules.

A violent “pampero” which blew two days after her departure made her lose two she-mules and, without undergoing other damages, it arrived thirty days later at destination, took there her full load of cocoa for Nantes and returned in the Loire forty five days later, on October 21st, 1898, finding along the way big bad southwest weather that tired the vessel.

On November 14th, charged with various goods for Pará, she waited on Saint-Nazaire’s natural harbour of favorable winds to disembogue from the estuary when she has been hit at anchorage by the English steamer Mersario, of Glasgow, which made her important damages.

She had to return in Penhoët’s dock to repair, going out again only on December 1st (…) [Louis Lacroix, 1945].

1898-1899, fifth voyage

Having been hit while anchored in front of Saint-Nazaire by an English steamship on November 14th, the Belem was immobilized 15 days for repairs of the damages.

Always commanded by the captain Dolu, she left directly for Belém on December 1st. She headed for the first time towards Martinique where she took a load of sugar and tafia for Nantes.

Having arrived at the retiring age, Captain Dolu, third commander of the Belem, settled definitively in Nantes.

She had to return in Penhoët’s dock for repairs, going out again only on December 1st for Pará which she reached in forty five days, leaving in the ballast for Martinique on February 8th, 1899. She cast anchor on the plateau of the lead lines of Saint-Pierre by a depth of twenty eight meters on March 1st, undergoing a quarantine of three days as coming from a contaminated country. The war had burst between the United States and Spain, obliging her to collect in the natural harbour of Fort-de-France what was left from her routed fleet and the Belem, who had to load at Pointe Simon, was not able to to approach until March 8; the Simon’s factory put more than a month to load him her with sugar and with tafia.

On May 28th, 1899, the captain Dolu moored his vessel to Les Salorges of Nantes and settled on ground, after a well filled life, full of honor and work, and thirty years of navigation. [Louis Lacroix, 1945].

Navigation

© 2001-2011 Laurent Gloaguen | dernière mise à jour : octobre 2016 | map | xhtml valide.